Report created by: Sean Moran, Dipo Rodipe, Dan Green, John Fitzpatrick

UK Ransomware

Trends 2022

JUMPSEC threat intelligence analysts have compiled a report tracking UK ransomware activity, focusing on attacks reported by ransomware groups themselves, and analysing the data to enable a more effective response to patterns as they develop.

Why we started

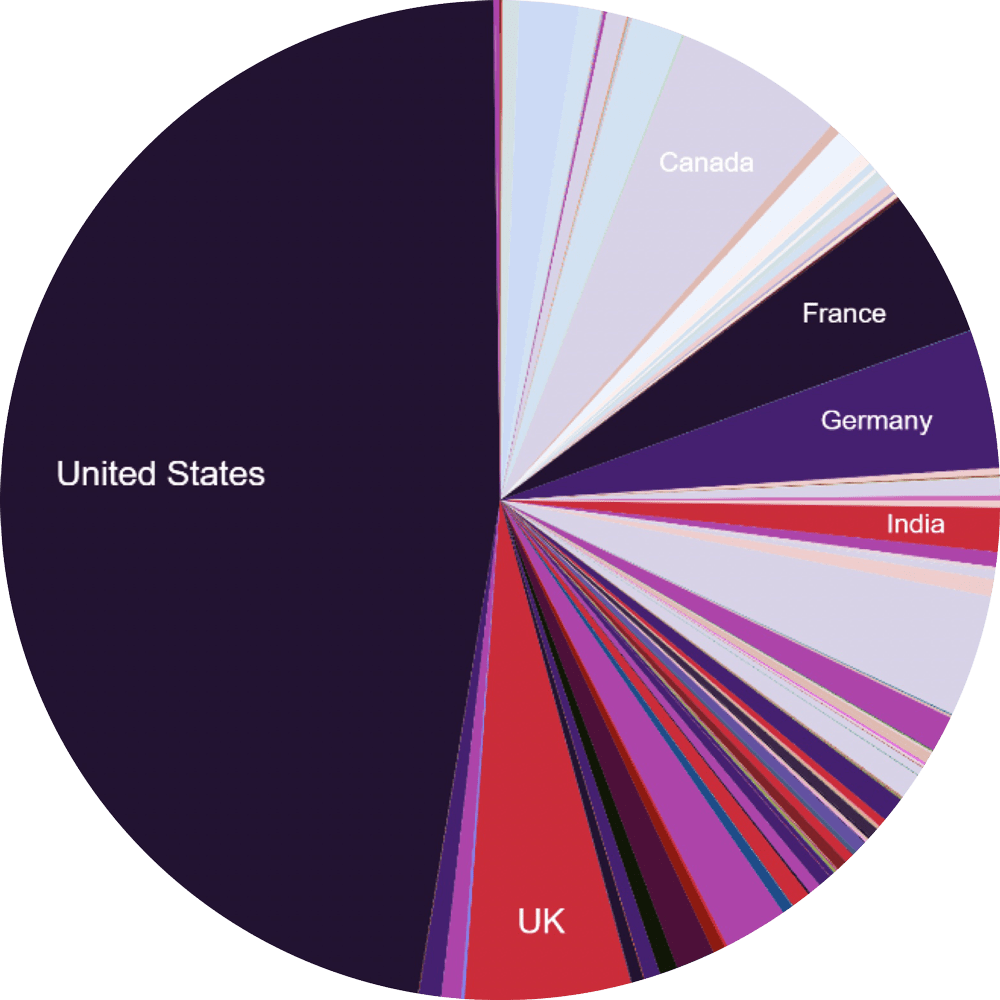

Analysis of ransomware activity is often focused on the US or provides a more global perspective, which expectedly skews the data and any insights that can be gained for UK-based organisations. This is understandable when considering the spread of ransomware activity globally.

The UK’s share of global activity has also been consistent, at just 5% of total global ransomware activity (shifting 0.1% over a year), with the UK representing 314 from a global total of 5,869 ransomware cases.

Percentage of total countries affected (UK~5%)

We took a UK-centric approach for this study, demonstrating the real impact of ransomware attacks in the UK since 2020. The data provides a range of perspectives including a breakdown of sector-by-sector prevalence, analysis of notable threat actors, and data on victim size, revenue, and profitability which may influence which UK organisations are targeted by ransomware attacks.

While statistics do exist (meaning those which are self-reported through public statements, surveys, and questionnaires) they are only a part of the overall picture. The missing piece can be established by looking more closely at what ransomware groups themselves are reporting. Lack of visibility and transparency of the real number of ransomware cases enables attackers to continually extort organisations while keeping the true extent of their impact hidden – from both security defenders and national policy-makers alike.

The UK Cyber Security Breaches Survey 2022 states that “enhanced cyber security leads to higher identification of attacks, suggesting that less cyber mature organisations in this space may be underreporting.” Whether intentional or not, underreporting ransomware incidents is an industrywide issue which this report aims to alleviate.

How we did it

JUMPSEC threat intelligence analysts have gathered data using a mixture of manual investigation and automated bots to search or ‘scrape’ the public-facing domains of the ransomware threat actors and openly available information for ransomware victims.

Where appropriate, we have compared and contrasted this information with officially reported statistics (such as the UK Cyber Security Breaches Survey), as well as exploring primary and secondary sources addressing the attacks claimed by ransomware actors (such as public statements made by alleged victims, or news articles reporting on the issue from sources close to the incident).

Why we took this approach

There is a clear incentive for organisations who are the victim of data theft and extortion to downplay the severity of a breach, as we explored in a recent article. Organisations have been known to claim the data stolen is outdated, particularly where data theft alone has occurred (without ransomware deployment) – making the attack significantly less visible, and therefore easier to brush under the carpet.

While this approach goes some way to bridge the gap between official and unreported statistics, gaps still exist. One of the primary limitations is that the available data is only based on what ransomware groups are reporting. Therefore, there is a potential gap where victims settle the issue before it hits the public eye (and therefore the breach is never reported, in official channels or otherwise). Attempts to track further data points, such as the crypto payments made to the wallets of ransomware actors, have been thwarted by the fact that there are simply too many wallets, too many operators, and too many currencies to build a useful picture in this manner.

Further, ransomware attacks are not necessarily perpetrated by a single organisation. Initial Access Brokers (IABs) provide a specialised service, gaining access to an organisation’s network and selling this access to the highest bidding ransomware group. Therefore, while particular ransomware groups may appear to prefer to target particular sectors or company sizes, or to have more success in a certain area, IABs may be equally as influential in dictating the trend of which organisations are targeted.

Despite these limitations, we believe a great deal of insight can be gathered from the data (lest perfect be the enemy of progress). We are continually looking to ways to improve the reach and accuracy of our data set by drawing on different information sources, and our analysis will evolve over time as a result.

1. UK Ransomware Trends in Context

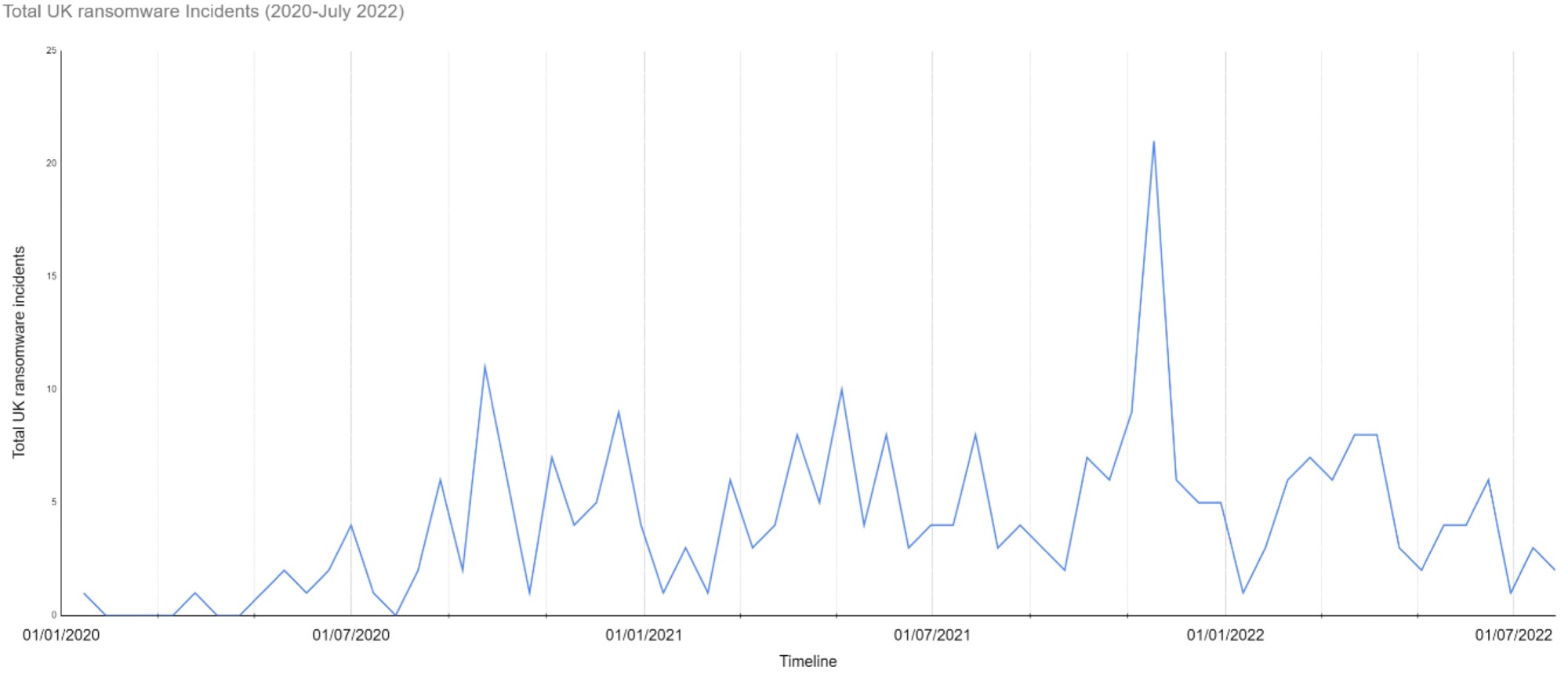

Ransomware as we know it today has been a persistent cyber threat globally since late 2019 and is a major concern for just about every organisation regardless of industry sector or business model, whether they possess the means to pay a ransom or not. The ransomware wave swelled periodically throughout 2020 and 2021, peaked, and then sharply dropped at the turn of 2022, with UK-specific figures following a similar pattern to global trends.

Total UK Ransomware incidents from 01/01/2020 to 01/04/2022.

Examining the data in detail often raises more questions than it answers. One point of contention that initially sparked debate between JUMPSEC analysts was if any reliable trends exist at all.

Ransomware-as-a-service exists in a chaotic and often unstable space, with groups subject to self-imposed shutdowns, internal splits, governmental crackdowns, and geo-political events which disrupt their operations. Add to this the widely accepted view that attacks are largely financially motivated, and one may opt for a simplistic narrative where random, money-grabbing opportunism is the sole contributing factor.

However, ransomware groups operate alarmingly professional business models, and in many ways trade on the same reliability and trust as legitimate businesses (as we have detailed here). Some notable patterns do become apparent, especially when we contextualise why certain groups have become more or less active, or consider the implications of real-world events on cybercriminal activity.

Just like legitimate businesses, ransomware groups’ raison d’être is financial gain – with a few notable exceptions. For example, we tracked an emerging ransomware group calling itself ‘AgainstTheWest’, who counterintuitively attack perceived enemies of the West and claim to operate on an ethical basis (and have even allegedly attacked UK-based Spark-Interfax), while the recent Conti group split during the Russia-Ukraine conflict proved ransomware attackers will not necessarily elevate financial gain above their politics.

Less provocatively (but perhaps more impactfully), new and emerging vulnerabilities are likely to increase the damage ransomware groups can inflict on organisations following their discovery and exploitation.

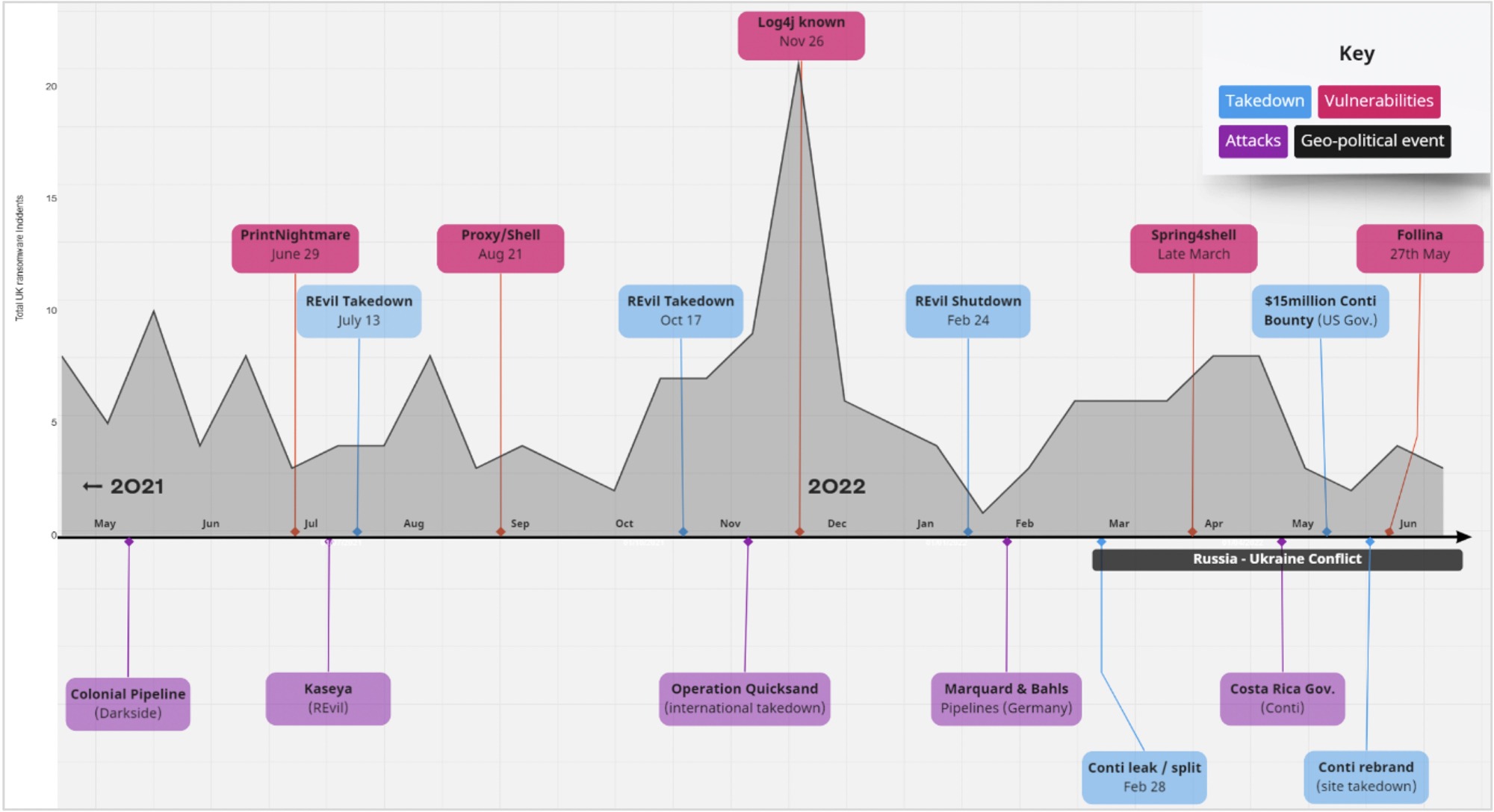

The graph below charts total ransomware activity in the UK, which shows an apparent correlation between points where well-known exploits were identified, and periods of increased attacker activity.

Total activity in the UK overlaid with a timeline of major cybersecurity events of the past 12 months.

Numerous high-profile vulnerabilities have been identified and exploited since the current ransomware wave began, most notably in 2021/22 PrintNightmare, Proxy/Shell, Log4j, Spring4Shell, and recently Follina.

A point we must consider here is the ‘dwell time’ attackers can spend on a network without detection. A 2022 report from Mandiant estimated the median dwell time for a ransomware attack in the Americas and EMEA as just 4 days, although dwell time estimations vary considerably across industry sectors and security maturity level (similar reports estimate as much as 11 days).

This indicates that attackers are performing end-to-end ransomware attacks in a much shorter period of time than historical attacks, reinforcing the importance of reacting and responding to emerging vulnerabilities in a timely manner.

It is also worth considering that the point that initial access was gained to the environment (likely through the efforts of an Initial Access Broker (IAB)) may be weeks or even months prior to malicious activity on the network beginning in earnest, as the various agents in the ransomware supply chain cooperate to distribute the access to interested parties.

One of the most pervasive vulnerabilities in recent memory, Log4j, surfaced on the 24th of November 2021, and while other factors may have been at play, it is perhaps no coincidence that our data shows UK ransomware activity reaching an all-time peak in December 2021, almost doubling the second highest spike in attacker-reported UK incidents to date. This does not mean other critical vulnerabilities were not also being exploited as Log4j came to light, but the emergence of Log4j is likely to have contributed to a rise in successful attacks.

Along with the influence of emerging vulnerabilities and geo-political events, a third influential factor is of course the action, or reaction, of law enforcement. These highly complex covert operations require immense planning and international cooperation, and in the case of REvil (formerly the fourth most active ransomware operators in the UK), the groups’ role in a seismic attacks disrupted national infrastructure and ruffled the feathers of powerful economic interests and high-rank law enforcement to the point of a very public shutdown in February 2022. Prior to the arrests, REvil also enacted several self-imposed shutdowns to reduce unwanted attention.

The REvil crackdown may seem like a drop in the ocean in the fight against ransomware, but it does demonstrate that targeting the wrong organisation in the wrong industry is a high-risk strategy for ransomware operators who want to evade the attention of authorities.

REvil’s shutdown and other operations like operation ‘Quicksand’, which took 19 law enforcement agencies in 17 countries over 5 years to execute, prove that with enough international cooperation and leverage ransomware groups can be combated. In this context, the Conti vs Costa Rica ransomware saga becomes all the more fascinating, with a total of 27 government agencies targeted by the Russian-based Conti. Costa Rica is the first country in history to declare a state of national emergency as a result of a cyber-attack.

The security industry may hope that Conti (the UK’s most prevalent threat to-date) has suffered the same fate as REvil, as the US Department of State offered a reward of up to $15 million for relevant information following the Costa Rican attack and, with the dissolution of current Conti brand at the end of May, some have celebrated the group’s apparent demise. However, Conti’s self-imposed shutdown is unlikely to stop the same individual hackers from re-applying their skills elsewhere and, as the group openly declared their support for Russia at the beginning of the Ukrainian conflict, the potential for internal law enforcement action or bilateral co-operation is now extremely unlikely.

Summary of the key factors influencing ransomware trends.

While the factors above all influence the threat landscape to a degree, the exploitation of vulnerabilities such as the recently discovered Follina are far more likely to impact ransomware trends than headline grabbing law enforcement action or changing geo-political dynamics.

Ransomware victims such as Tuckers demonstrate the impact that an ineffective patch management programme can have. Tuckers was fined £98,000 in the wake of the breach, for which the ICO criticised their failure to install critical updates for ~5 months.

As organisations move to implement effective controls and diligently patch vulnerabilities, the burden should not solely lie with individual organisations. Third-party providers of software should also be expected to minimise the time between a zero-day vulnerability’s discovery and the release of an effective patch – acknowledging that by the time of becoming aware of an issue, the issue has likely already been exploited in the wild.

Current studies estimate the time elapsed between initial 0-day exploitation and patch release at 9 days. PrintNightmare took a relatively speedy 7 days to patch, while the recent Follina vulnerability took 18 days. That said, the Log4j patches resulted in further security issues being introduced, compromising the efficacy of the fix – indicating that patch efficacy is equally as important as speed.

2. UK Sector-by-Sector Analysis

At first glance one may assume that particular attackers favour specific industries, influenced by perceived lower levels of cyber maturity or the promise of a more lucrative potential payoff. For example, a UK law firm may fear they will be targeted because hackers understand how damaging a breach would be to their reputation, or a manufacturing executive may worry if a recent boom in revenue could attract attention from cyber criminals.

In reality, it is difficult to infer exactly why ransomware groups attack particular organisations. Sector-by-sector analysis may not reveal much about the pathology of attackers, but it does reveal something about the degree to which even random ransomware hackers have been able to exploit particular sectors.

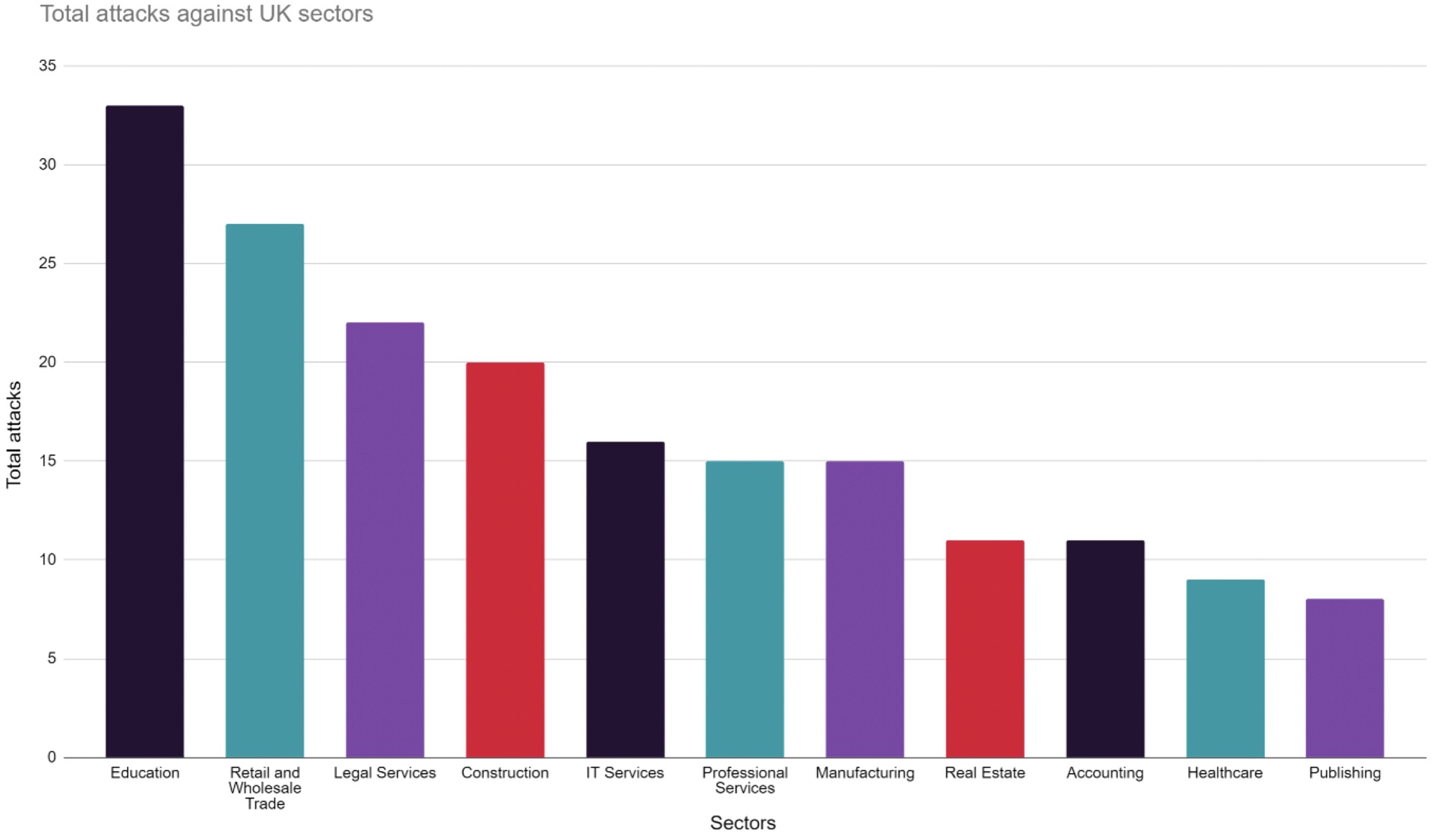

Which begs the question – how often have different UK sectors reportedly been hit over the past year?

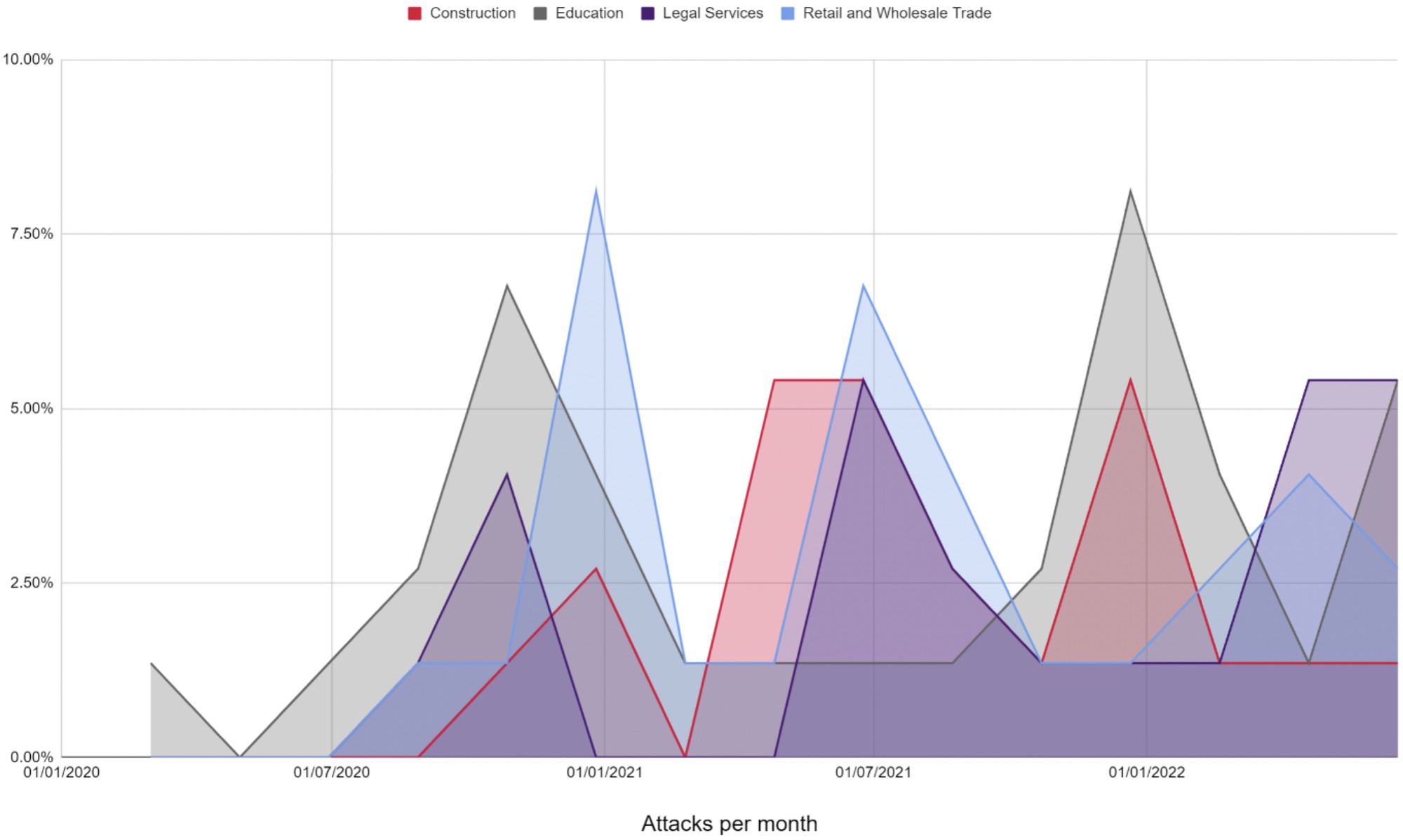

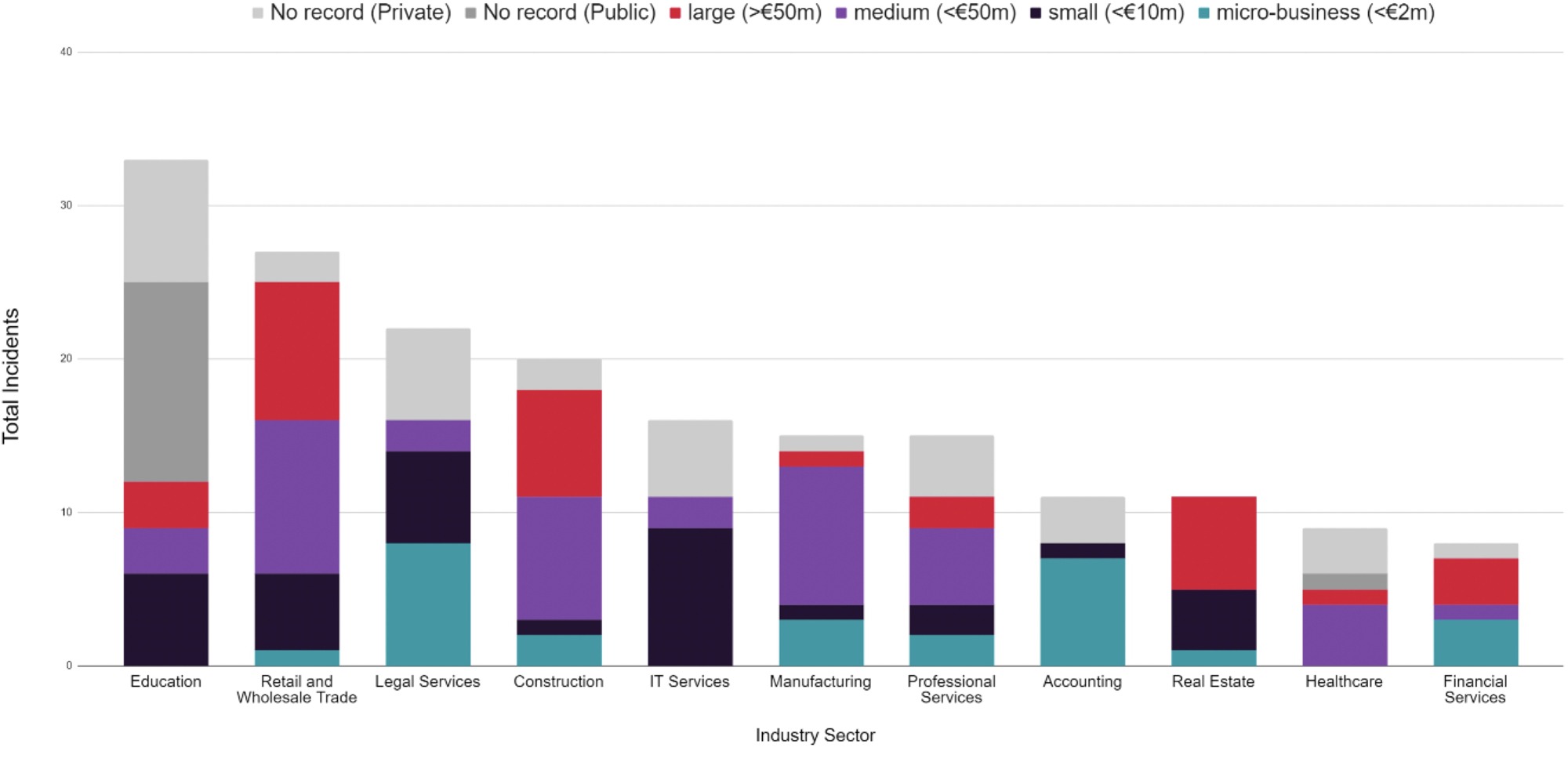

The data suggests that Education, Retail and Wholesale Trade and Law are the most targeted industries, but we must examine the financial size and capacity of victimised organisation to gain a more realistic insight on the true sector-by-sector impact of ransomware in the UK.

Simply counting the total number attacks is misleading. For example, the Legal Sector appears to be the third most victimised industry in the UK, however the sector’s combined cash in the bank assets is one of the lowest of the industries included above at just £5.39 million, as compared to a massive £198m for the Construction industry and £337m for Retail and Wholesale Trade. Further analysis of the financial status of victims is provided later.

JUMPSEC’s initial analysis broadly aligns with the most recent UK Cyber Security Breaches Survey 2022, showing a striking number of ransomware attacks against the UK Education sector, which is disproportionately victimised in the UK compared to the rest of the world. Educational institutions may not have pipelines that can be shut down or factories whose systems can be disabled, but they do rely heavily on online learning software and exam and coursework submission portals exposed to the public internet. Higher Education institutions also make particularly viable targets as they store sensitive data and valuable IP.

How successful attackers have been in some of the UK’s most victimised sectors since 2020. These trends are broadly consistent with total attack rates in the same period.

The data here seems to indicate that sectors go through periods of increased and decreased targeting from attackers – perhaps pointing to concerted attacker efforts against particular sectors over time.

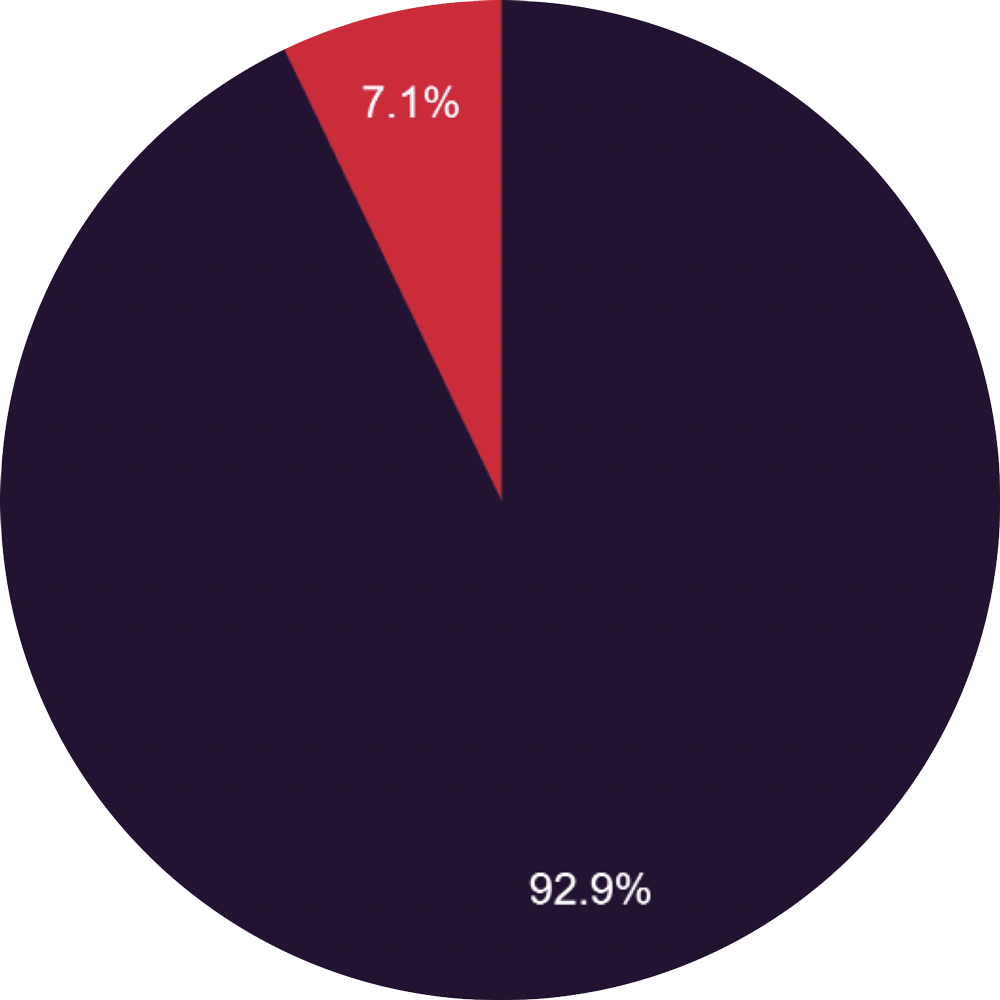

It is also worth noting that attacks in the private sector are dominant, despite a large proportion of attacks in some sectors involving public institutions (e.g. Education).

Public vs Private Sector Breakdown.

- Private Sector

- Public Sector

The sector-by-sector graphs presented thus far only scratch the surface of ransomware’s impact in the UK, as a larger number of extortion attempts does not necessarily translate to more financial success.

More telling insights can be gleaned from the financial breakdown below, as we explore the financial capacity of highly victimised sectors, their relative vulnerability, and their ability or willingness to actually pay a ransom.

Does size matter?

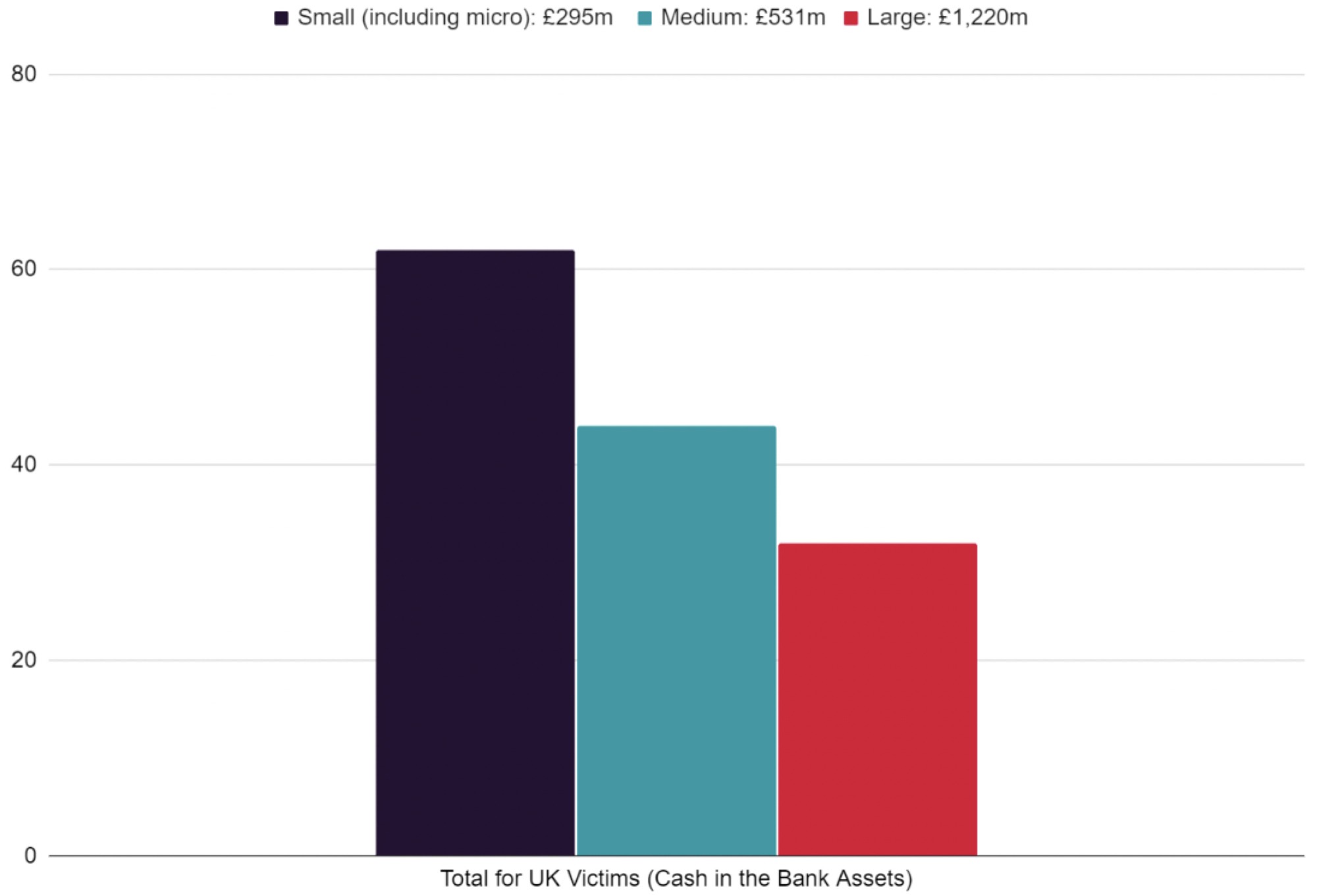

An initial glance at the data might lead to the conclusion that small businesses (in terms of their financial status) are being targeted over medium or large scale enterprises.

Although small businesses are naturally targeted more frequently (as there are simply more of them) their accumulative Cash in the Bank Assets of £295 million are only a fraction of medium (£531 million) and large businesses (£1.22 billion) Cash in the Bank Assets – explored in further detail below.

A small business may assume that they will not be targeted because they are a comparatively low-return target, as the ransoms levied by criminals are typically tailored to the nature of the victim. However, the data suggests that smaller organisations need to be equally as attentive to the state of their current cyber defences as larger organisations. Larger businesses on the other hand should treat their supply chain (of typically smaller, less mature businesses) as a part of their own organisation’s digital footprint and look to leverage their security resources to support and uplift the resilience of the supply chain.

Simply vetting suppliers with self-serve due diligence is not enough to tackle the scale of the security challenge that smaller organisations operating as part of a supply chain face. Collective security initiatives that enable smaller organisations to leverage the resources and capabilities of their larger partners can go some way to increasing supply chain resilience.

That said; there are simply more small/micro businesses in the UK (99.2% of UK businesses according to gov.uk) than there are large or medium sized businesses. Therefore, it is likely that small businesses are not being specifically targeted, but rather that they are generally less resilient to attack and more susceptible to opportunistic compromise.

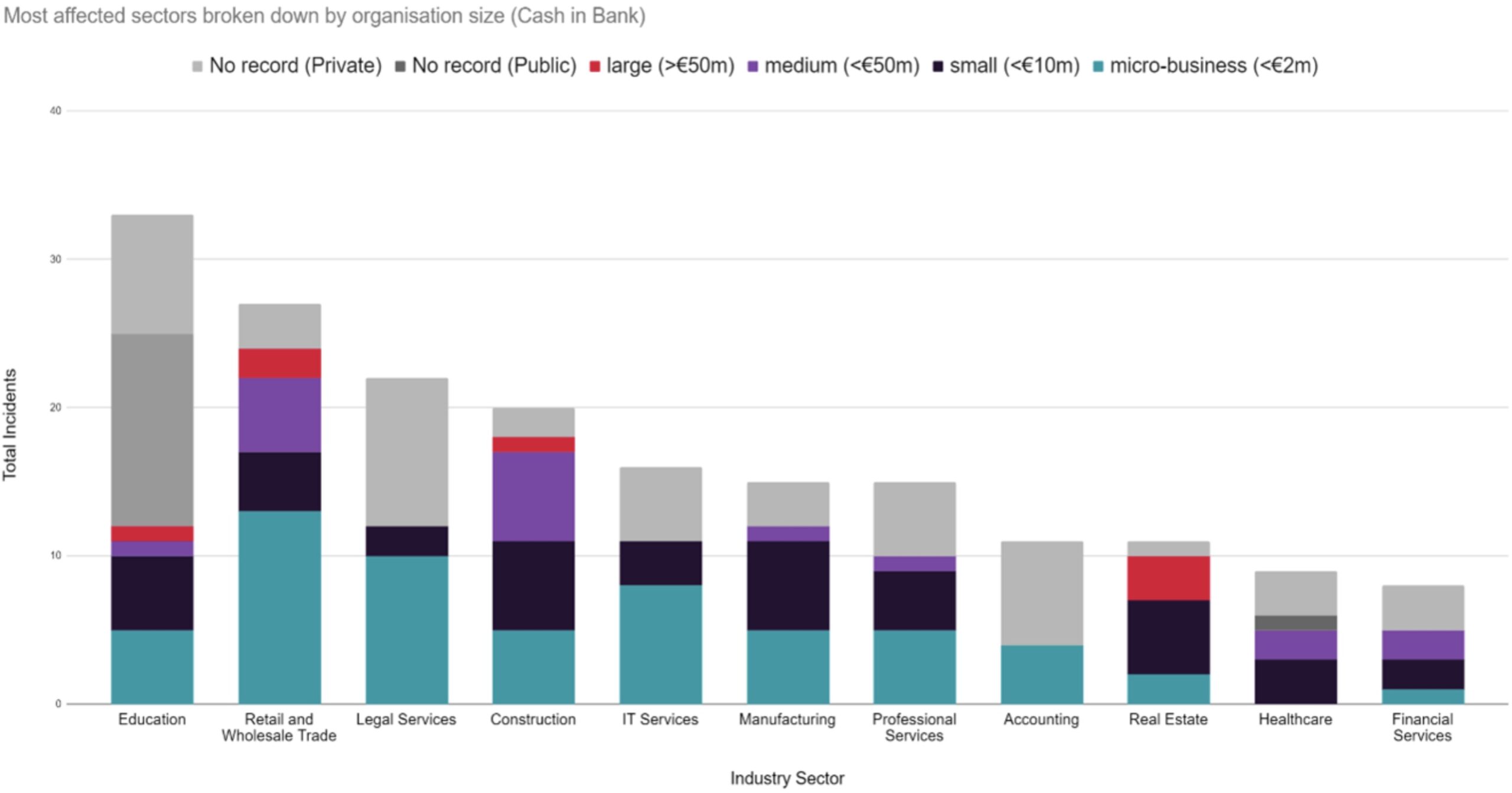

When we break down small (and ‘micro-businesses’), medium and large organisations that have been targeted in the most victimised sectors, the results further demonstrate the impact of business size over the total number of attacks an industry experiences.

Some key points to consider from the graphs and figures below include:

- The most lucrative industry to target hypothetically is Retail and Wholesale Trade, owing to its high number of large sized victims (>€50m). This omits Education which has a higher proportion of unavailable public financial data than other sectors.

- Construction may be a highly lucrative sector to target, with the largest proportion of medium-sized organisations, totalling £198m Cash in the Bank assets collectively.

- Real Estate is potentially a highly lucrative industry to target despite a relatively low attack rate, with a combined total of over £118m cash in the bank, due to the high proportion of large-sized victims within the Real Estate sector.

- There appears to be a high proportion of micro-businesses attacked in the Wholesale Trade, Legal, and IT Services sectors – perhaps owing to the fact that a greater number of small businesses make up the overall demographic within these sectors.

A breakdown of the UK’s most victimised sectors by ‘Cash in the Bank’ and ‘Total Assets’. This metric hypothetically indicates a greater ability to pay, potentially making them more desirable targets – unless an organisations’ net assets are in poor condition (i.e. they are in debt). The UK still classifies companies in Euros (€) as per this report.

Most affected sectors broken down by organisation size. (Cash in Bank)

Most affected sectors broken down by organisation size. (Total Assets)

We know that Ransomware groups and Initial Access Brokers (IABs) have become increasingly professional. There is potentially some evidence to suggest that attackers are aware of the financial viability of their victims. We evaluated the financial status of the victims we identified to draw a picture of the most lucrative sectors to target from within the data set. Interestingly, this broadly correlates with the most victimised sectors represented in the graph above.

Of the most highly targeted industries, Retail and Wholesale Trade seems to represent the most lucrative target in terms of both Cash in the Bank and Total Assets. Cash in the Bank assets is the leading metric when assessing an organisation’s ability to pay a ransom, with some exceptions. For example, if an organisation’s net assets are in the red (i.e. they are in debt or are financially insolvent), the organisation would perhaps be less able to pay despite their cash assets.

| Industry | Total Cash in the Bank | Total Assets |

|---|---|---|

| Retail and Wholesale Trade | £368,521,830 | £2,473,230,100 |

| Construction | £198,771,340 | £744,351,950 |

| Real Estate | £165,175,130 | £5,325,100,000 |

| Education | £89,556,140 | £949,350,000 |

| Financial Services | £62,763,010 | £304,548,820 |

| Manufacturing | £54,984,360 | £367,352,770 |

| Healthcare | £36,220,000 | £149,220,000 |

| Professional Services | £32,097,12 | £213,152,090 |

| IT Services | £13,091,660 | £96,600,000 |

| Legal Services | £7,827,010 | £68,502,651 |

| Accounting | £1,701,830 | £6,097,312 |

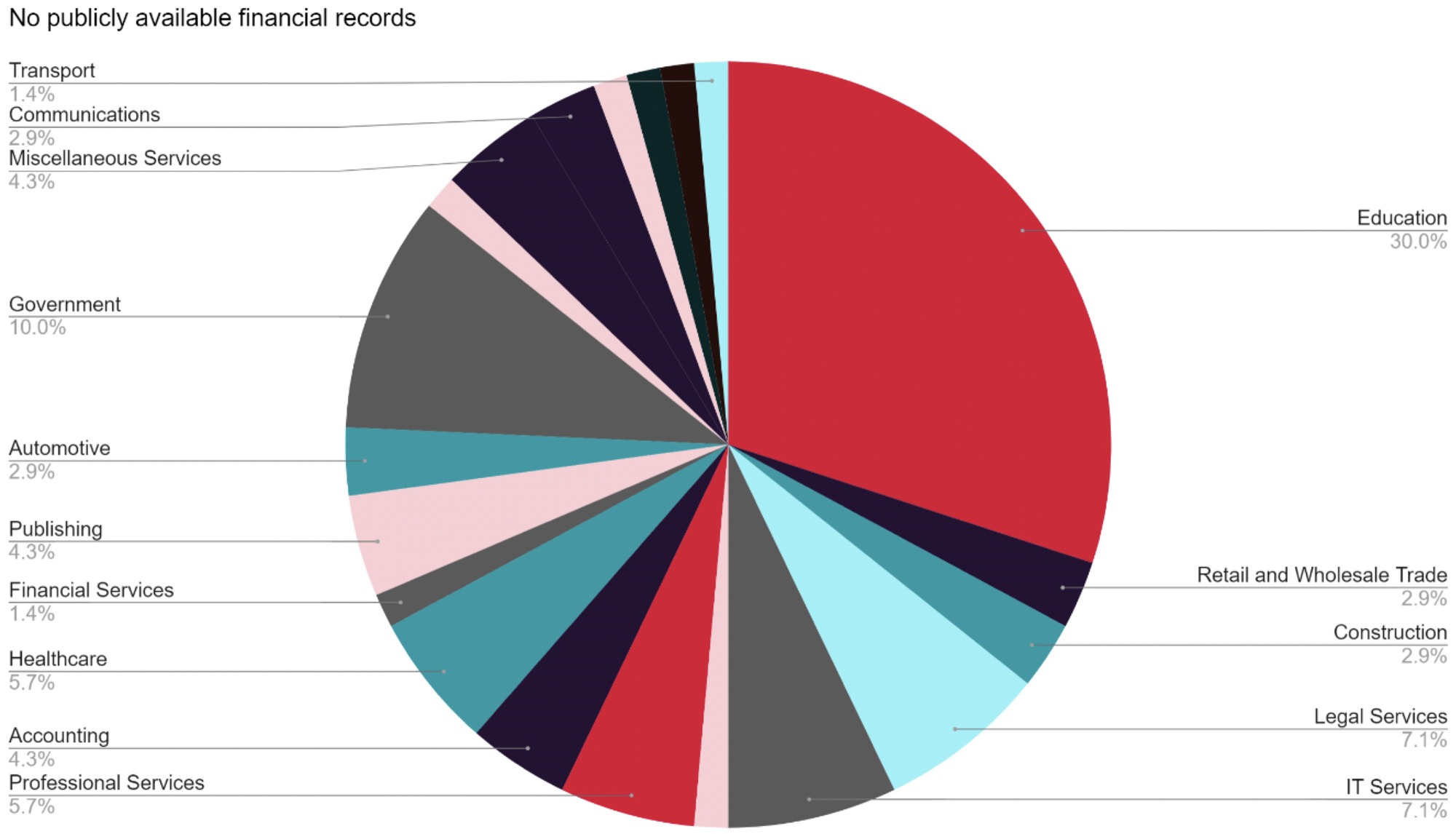

A number of the entries did not have financial information available online. The proportion of organisations with no publicly available financial data is similar across industries with the exception of education – due to a higher number of public sector institutions who do not publish data, and a disproportionately higher number of private education organisations with no available data.

Sector-by-sector breakdown of organisations who do not have financial data publicly available.

No publicly available financial records.

A note on supply chain risk

According to the latest gov.uk Cyber Security Breaches Survey 2022, only 13% of businesses assessed the risks posed by their immediate suppliers, with organisations saying that cyber security was not an important factor in the procurement process, due to the businesses outsourcing their IT and cyber security (approximately 58%). The aforementioned Kaseya ransomware attack is a prime example of the potential damage a supply chain breach can have.

Many of the smaller organisations victimised are likely to form a part of many enterprise supply chains – particularly in sectors such as Financial Services, Accounting, Professional Services, Legal, and IT. An organisation is only as secure as its weakest supplier. Therefore, all organisations must reduce their risk exposure by conducting careful due diligence on their suppliers and subcontractors. More cyber-mature businesses should require suppliers to meet GDPR, governance, and compliance requirements, encouraging less mature organisations to improve their posture while reducing risk of compromise via their supply chain.

3. Ransomware Groups active in the UK

The UK’s most wanted

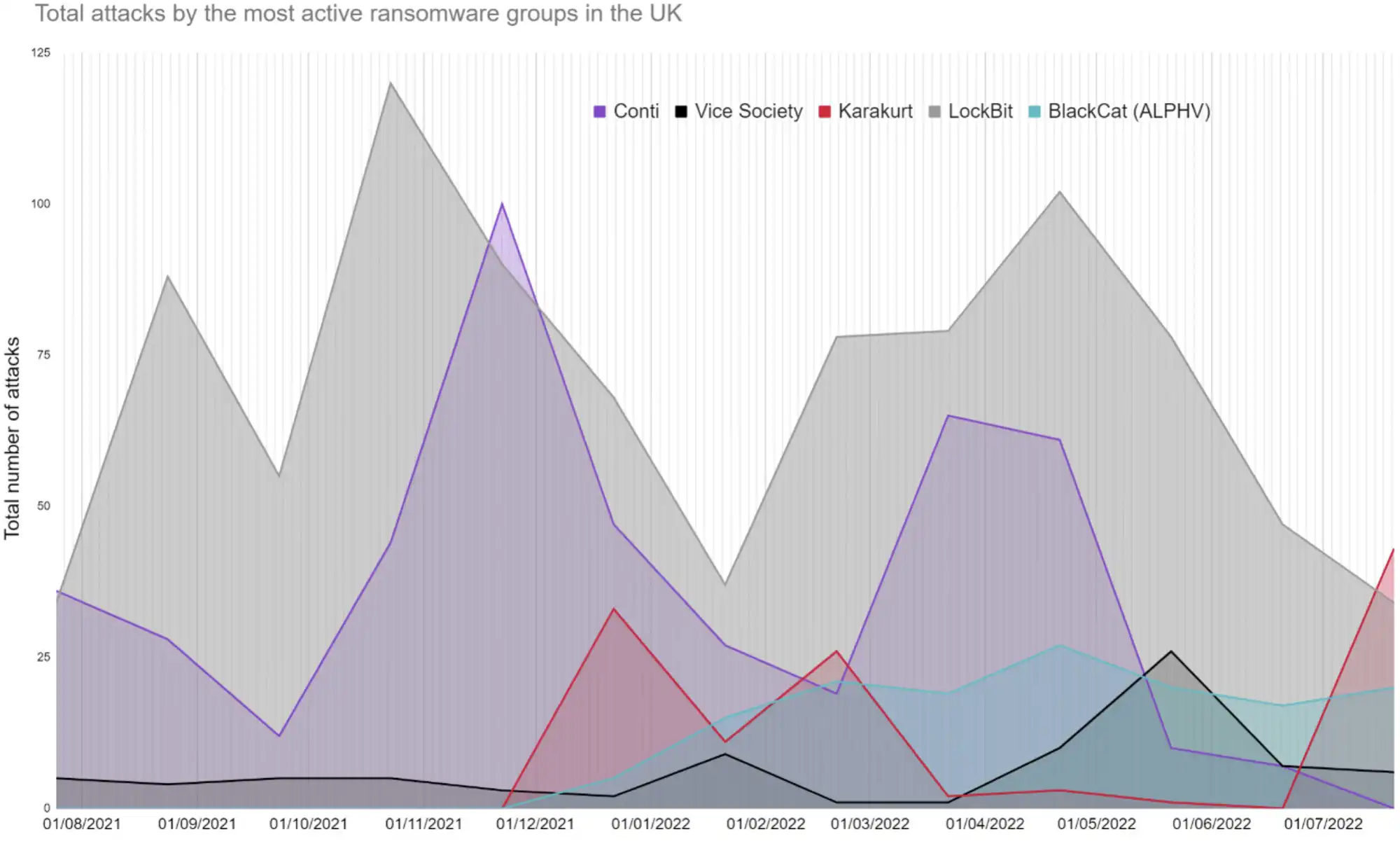

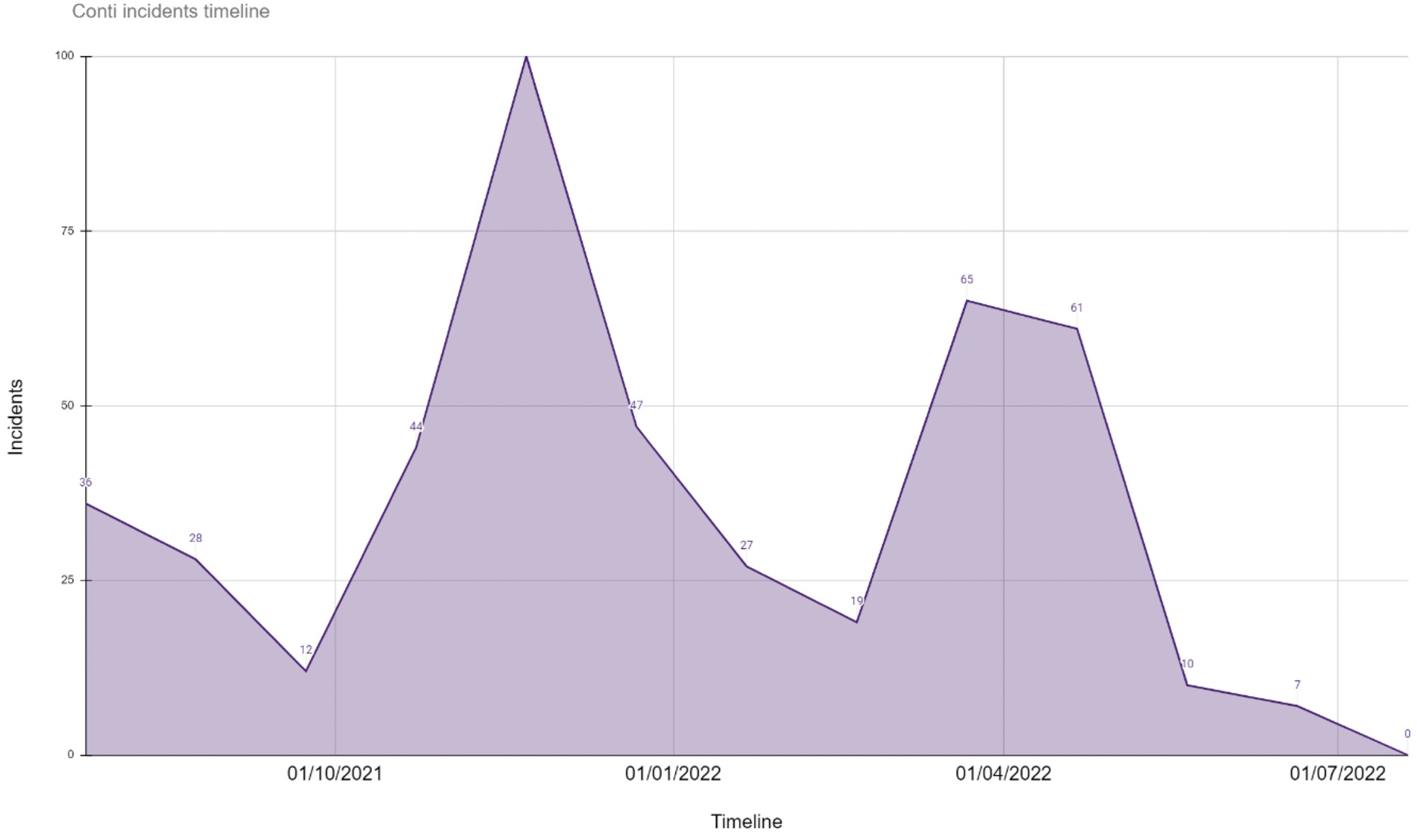

The most prevalent ransomware group in the UK since the current ransomware wave began in 2020 has been Conti, closely followed by LockBit. As with total UK attack figures, we saw a drop in overall activity at the end of December, before an uptake in attacks through March and April. While the total figures show Conti as the UK’s top attacker, LockBit are now likely to become the most prevalent threat to UK businesses going forward.

Charting the total activity of the 5 most prevalent ransomware groups in the UK (as of 2022). While our objective is not to humanise ransomware criminals our data suggests they may at least celebrate Christmas.

The trajectory of Conti has been fascinating to follow over the past few months. The group first split internally due to Russia-Ukraine conflict in March, then conducted an unprecedented attack against the government of Costa Rica a month later, before finally shutting down its brand completely at the end of June. Our data reflects Conti’s apparent decline. However, the groups’ official disappearance does not mean that the same hackers are not reapplying their skills, perhaps with groups like Karakurt for example – who have been linked to Conti and have become an increasingly prolific threat.

Ransomware groups are not necessesarily fixed entities, with groups rebranding, disappearing and resurfacing overtime. For example: Sodinokibi (AKA REvil) and BlackMatter (linked to Darkside and REvil) amongst others. While knowing your enemy is important, the lines between groups can be blurred. There have even been recent reports that Russian based REvil (taken down in Febuary 2022) returned to business as usual in April 2022, perhaps unsurprising given the Russian–Ukraine conflict.

LockBit have been the second most consistent threat to UK businesses from 2020 to present. Unlike Conti however, LockBit do not appear to be dissolving anytime soon. In fact, the group recently announced a bug bounty programme or ‘LockBit 3.0’, which may signal an even more professional era for ransomware-as-a-service, offering financial rewards to hackers who can identify vulnerabilities in their malware or offer the group fresh ideas – a practice borrowed from legitimate businesses.

Conti disproportionately attacked the UK and are the largest threat to-date; however, this is changing.

As Conti’s reported shutdown suggested, the group have not claimed any attacks since early July.

As of July 2022, two of the most notorious groups, REvil and Conti, have been essentially shutdown after drawing too much attention from international law enforcement (or more specifically the US authorities, who appear to have had some impact on major ransomware groups’ activities).

The contrast between recent public announcement from the UK with that of the US authorities is striking. In the previously mentioned Conti vs Costa Rica ransomware attack, the US issued a $15 million reward for information to help take Conti down.

Two weeks later, the UK attorney general set out the UK’s position on cybersecurity by releasing a self-congratulatory press release, centred on a list of occasions where the UK have publicly ‘named and shamed’ attackers. Notably, this release did not mention any occasion where they have actually taken down an active threat.

One might ask if UK authorities are doing enough to protect UK organisations, especially as ransomware groups and their technologies evolve into increasingly professional and persistent threats. However, the chaotic nature of ransomware-as-a-service, and attackers’ ability to rebrand and reinvent themselves severely limits even the most successful law enforcement efforts.

4. What have the victims said?

Ransomware attacks have been a persistent threat for UK organisations since early 2020, with JUMPSEC’s data showing a total of 294 attacker-reported incidents to date (from 2020 – August 2022). In response to this influx of attacks, JUMPSEC tracked each attacker-reported incident, and analysed how UK victim organisations have reported (or all too often not reported) cyber-attacks where ransomware operators have attempted to extort their organisation.

Being open and honest is always the right way to handle an attack. Not simply on a principled or moral level, but as the safest way to avoid legal ramifications, GDPR penalties, and risk to customers and suppliers.

By law organisations must report an attack to ICO (and are advised to report to NCSC) if the attack reaches a certain severity threshold (i.e. it impacts their operations). This reporting is also done anonymously. Whilst this information is accessible, it is not readily available or openly shared, preventing organisations which face similar threats from properly learning from prior incidents.

The unwillingness of victim organisations to ‘own it’ when an attack happens is also skewing the real number of ransomware cases nationally; enabling attackers to continually extort organisations while keeping the true extent of their impact hidden from both security defenders and policymakers.

Our findings

JUMPSEC’s data shows that:

- 86% of UK ransomware attacks go completely unreported in typical media sources.

- Even amongst the remaining 14% of reported cases, many organisations only admit a breach has occurred after being outed by attackers online, or do not report the attack directly via their own website.

- Finally, <2% of the total victims discussed the attack in any meaningful detail (such as by outlining the breach vector leveraged by attackers).

JUMPSEC’s findings relating to attacks reported in the media are tabled below.

| Metric | Results |

|---|---|

| Posted by attackers before appearing in the media | 60% |

| Reported it on a 1st party website | 33% |

| Posted by the media before reported by attackers | 28% |

| Said the attack was “sophisticated” | 21% |

| Media and attacker posted on the same day | 12% |

| Named a breach vector | 10% |

Notable exceptions

While in the minority, some organisations have responded quickly and transparently when attacked, precisely as they should have. One such example is the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA), who published a detailed report on the attack methods deployed, a detailed timeline of events, and how the agency have since restructured their cyber operations and strategy since the attack.

By being forthcoming with their direct experience SEPA did more than acknowledge the attack. They evidenced that they had met and exceeded cyber security best practices, and demonstrated their willingness to further enhance their security posture through the opportunity provided by the incident. SEPA also made it abundantly clear that they did not use public money to pay the ransom, even when faced with a decimated accounting system (with £42 million unaccounted for) and the loss of basic network functions such as email.

Realistically, not every organisation will release a 30-page report as SEPA have. Nonetheless, organisations can learn from their pro-active approach, which has not only aided fellow security researchers but served to reputationally reposition the organisation in a positive direction after such a damaging scandal.

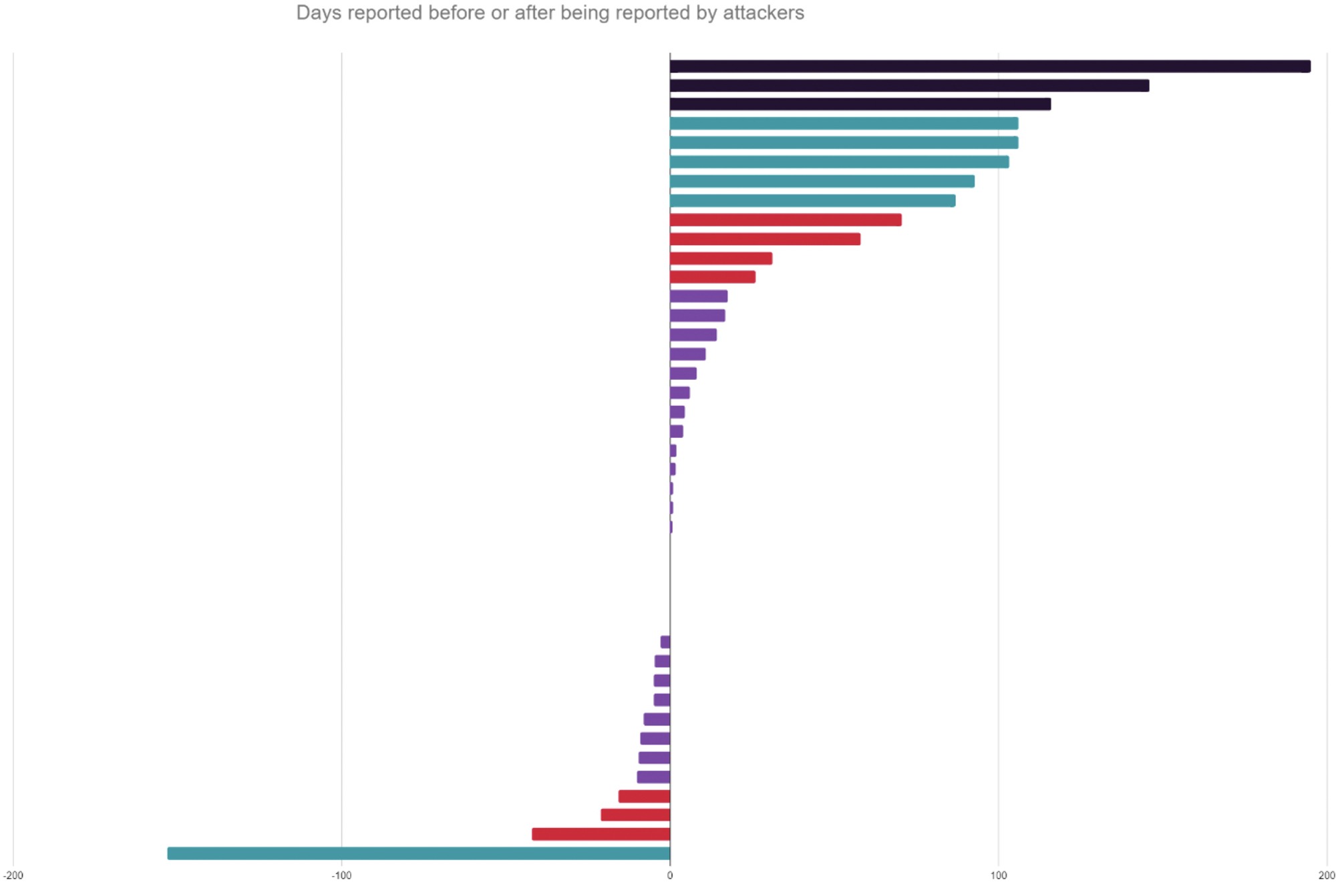

Who goes public first?

Ransomware attackers posted attacks on their own sites before the victims or media 60% of the time.

JUMPSEC’s data shows that ransomware attackers are generally the first to go public about a breach, as they attempt to pressure the victim organisation to pay the ransom, or to peddle stolen sensitive data to prospective buyers (e.g. personal credentials and intellectual property).

Either the attackers, the victim organisation, or in some cases the media (when the attack is of a sizable scope and scale) will naturally report the attack in a particular order.

- The attacker reports first. This may indicate that the victim organisation has not been proactive in disclosing the issue, as the organisation is likely to have known about the attack and stayed silent – on some occasions for several weeks.

- The victim organisation reports first. Whilst an organisation proactively acknowledging an attack is the most commendable scenario in theory, some attacks may be so severe that the attacker has left the victim no choice but to acknowledge it in the media due to obvious disruption to their operations.

- The media reports first. In many cases, often due to the sheer size or notoriety of the victimised organisation, the attack is impossible to hide from media attention as the impact of the attack may be reported by affected customers or employees before the victim formally comes forward.

JUMPSEC’s analysis (see figure) shows that most organisations have already known about the attack for some time before acknowledging it in the media. Proactive reporting by a victim before the attack is claimed by a ransomware group also tends to correlate with the severity of the attack. The fact that attackers do not urgently claim attacks at the time the attack occurs perhaps indicates that they may use public non-disclosure as leverage when trying to extort a ransom payment. It could also simply suggest that they leave the admin of claiming a victim until later.

The time elapsed between the attacker going public about a breach, and the victim organisation publically acknowleging the attack.

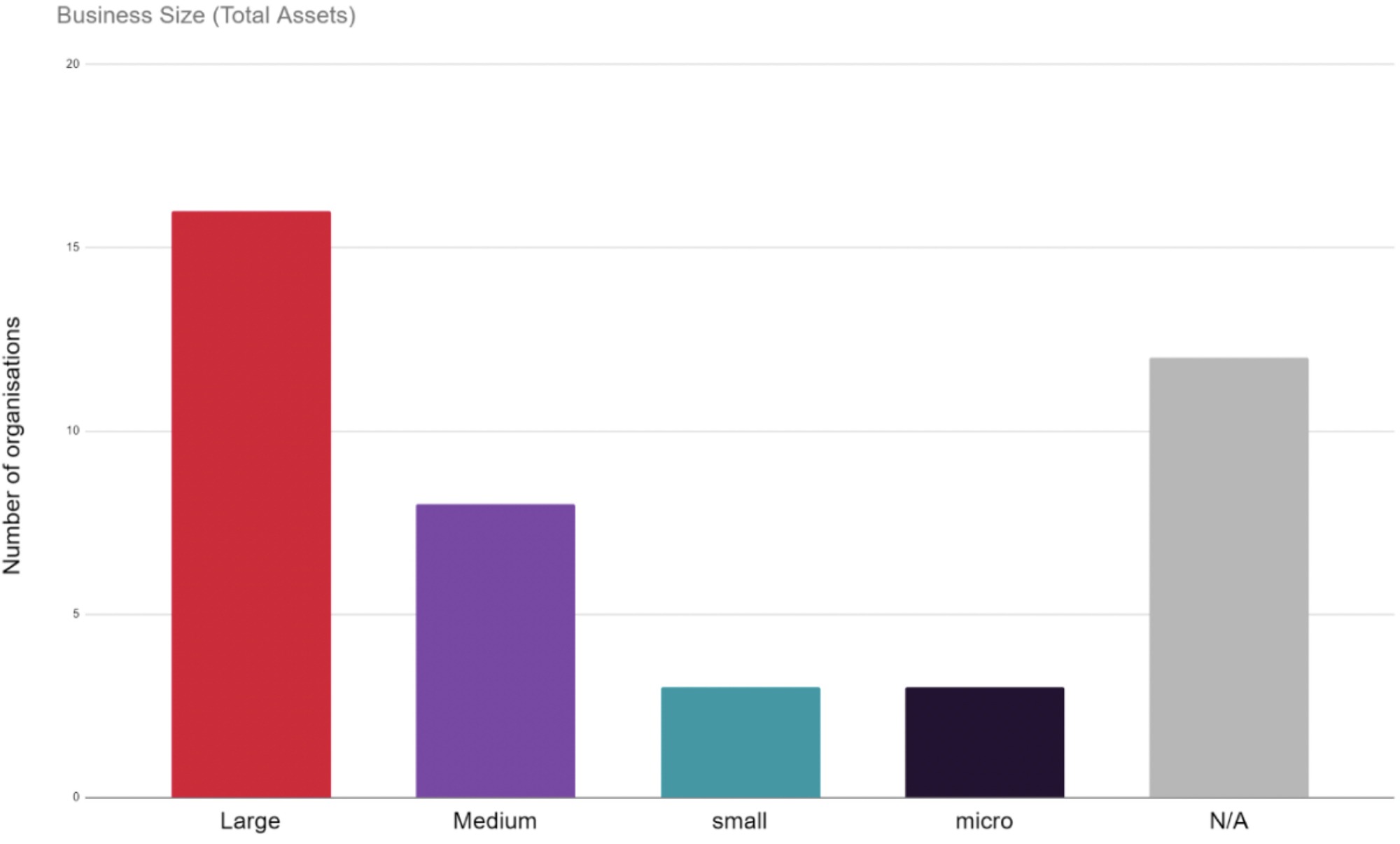

Does reporting correlate with victim size?

Large organisations represent 38% of organisations or media-reported attacks, despite being only 20% of the total number of organisations identified by JUMPSEC as victims of ransomware attack.

JUMPSEC’s data shows there have been significantly more ransomware attacks against smaller UK organisations than large and medium organisations in terms of sheer total attack numbers. However, large organisations are still far more likely to report a ransomware incident, or have one reported in the media.

A breakdown of incidents reported in the media by small, medium, and large size organisations. Large organisations are far more likely to report an incident publicly, or have an incident reported in the media.

Attacks on larger organisations naturally impact more people and businesses, making them more newsworthy and more difficult to ignore. This also makes them more likely to report incidents on their own sites, with large organisations making up 36% of the organisations reporting on their own website.

5. Sign up for Quarterly Ransomware Updates

"*" indicates required fields