JUMPSEC Ransomware Hub reports are based on over 9,000 data points from over 100 data leak sites tracked by our threat intelligence analysts from 2019 to present.

JUMPSEC have recently tracked a data leak site variant called UnSafeLeaks.

UnSafeLeaks’ tendency to target senior leadership and other prominent employees with malicious blog posts sets it apart from typical ransomware sites, which thus far have taken a more transactional approach to achieve purely financial objectives. Several organisations targeted by UnSafeLeaks have also been previously compromised by affiliated ransomware groups, suggesting the potential re-extortion of victims.

With these unique factors at play, UnSafeLeaks presents an emerging threat that has yet to be clearly defined. Terms like ‘double’, ‘triple’ and even ‘quadruple extortion’ have been coined to describe attacks where ransomware groups simultaneously exfiltrate sensitive data, use subsequent DDoS attacks, or notify victims’ clients and suppliers to intensify the pressure to pay.

However, UnSafeLeaks are not actively leveraging victims’ encrypted networks or disrupted operations to achieve their objectives. Perhaps more accurately described as compound extortion – organisations that have already fallen victim to ransomware now face unforeseen repercussions months after an initial attack, and to compound the situation, individual employees or senior leadership are being targeted in malicious campaigns of personal defamation.

Why UnSafeLeaks is different

Up to now data leak sites have served two primary functions:

- Attracting potential ‘affiliate’ threat actors to use their Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) offering.

- Publicly exposing and extorting victim organisations with explicit demands for bitcoin payments, accompanied by the public threats to leak data if demands are not met by a specific deadline.

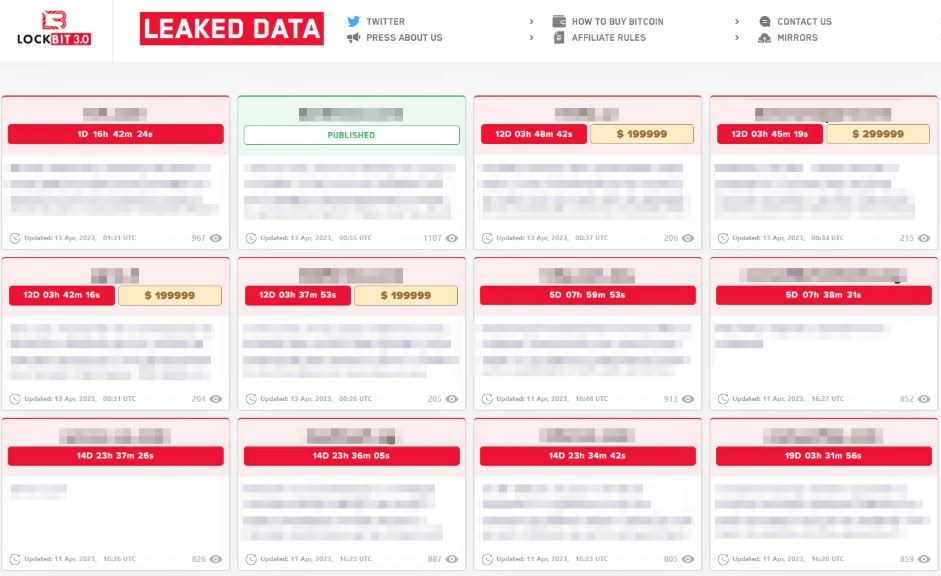

A typical data leak site containing demands for specified ransom fees (Lockbit ransomware).

At a glance no different from a typical leak site. UnSafeLeaks however do not outline a fixed crypto fee or give victims a time limit to pay before their data is leaked.

Insult to injury

Many of UnSafeLeaks’ posts read more like the words of a schoolyard bully than a calculated ransomware group focused on profits, commenting on a prominent CEO’s divorce, implying evidence of sexually explicit images, referring to drug use by senior stakeholders, and drawing connections between corporate executives and prominent political figures.

JUMPSEC have chosen not to name individuals or organisations by quoting UnSafeLeaks directly. JUMPSEC can however confirm sample data provided as proof does include sensitive images and documentation.

Up to now, ransomware threat actors have generally presented themselves to victims as helpfully identifying a network vulnerability (much like a legitimate third-party security provider), adopting a transactional tone to persuade breached organisations that they will amicably part ways once a payment is received. UnSafeLeaks’ shift towards targeting an organisation’s senior leadership represents a significant change.

Who are UnSafeLeaks?

Upon analysis of targeted organisations, JUMPSEC have identified that the majority of victims targeted by UnSafeLeaks were compromised in ransomware attacks dating as far back as early 2021, predominantly by two groups – REvil (Sodinokibi) or BlackCat (ALPHV). The remaining target organisations were previously compromised but avoided publicity and have never featured on data leak sites, indicating they are now likely being re-extorted after paying a ransom.

To rewind for a moment, Russian based REvil were arguably the most notorious and impactful ransomware groups globally, claiming high-profile attacks on the Colonial Pipeline, IT provider Kaseya and Apple, amongst others, prior to a well-orchestrated public shutdown in 2021. Since then, numerous groups have been dubbed as REvil spin offs, most notably BlackCat (ALPHV) who have risen to prominence in 2022 and 2023 by targeting a number of high-profile organisations.

Both REvil and BlackCat are no strangers to innovating with novel extortion strategies. REvil pioneered a number of double and triple extortion tactics while BlackCat recently launched a search function to make it easier to find victims or even specific details on the clearnet (i.e not the darknet).

And in an ominously prophetic nod to upcoming extortion tactics in a 2021 interview prior their shut down, a REvil member stated:

“We call each target as well as their partners and journalists—the pressure increases significantly [i.e ‘triple extortion’]. I also think we will expand this tactic to persecution of the CEO and/or founder of the company. Personal OSINT, bullying. I think this will also be a very fun option. But victims need to understand that the more resources we spend before your ransom is paid—all this will be included in the cost of the service.”

Whoever the orchestrators, UnSafeLeaks are likely one of, or a combination of, the following:

- An off shoot from an established ransomware group (i.e REvil or BlackCat) seeking to cash in on prior breaches or, an ‘un-official’ side project for individual members.

- A connected threat actor with political motivations and explicit or tacit state support (a number of posts draw political connections where they exist).

- Part of a coordinated attempt to extort targeted individuals by contacting them privately and issuing ransom demands – the next phase of the “Personal OSINT” outlined by REvil as a new extortion tactic.

- A technically limited individual or group with access to data posting increasingly defamatory content as UnSafeLeaks do not have the same leverage as a ransomware group who are actively encrypting a victim’s network. Sensationalising the data may create its primary value in the marketplace.

UnSafeLeaks are not unequivocally the same individuals behind REvil, BlackCat or other affiliate threat actors. And, while these likely connections provide ample interest for speculation, identifying precisely who UnSafeLeaks are is not the crucial point here.

UnSafeLeaks exemplifies a broader trend toward highly personal attacks on individuals within targeted organisations, but perhaps more importantly, if replicated, the widespread compound extortion of victim organisations would disrupt the existing dynamic of the ransomware eco-system, which trades on the idea that paying a ransom is worth it – because once you pay, you will be left alone.

Undermining or enhancing ‘established’ ransomware?

UnSafeLeaks are re-purposing pre-hacked data, but at what cost to ransomware in the long run?

As ransomware groups rely on the flow of crypto payments from target organisations, often backed by their insurers, the more organisations who recognise that paying a ransom will not reliably keep data private, the less paying a ransom will be viewed as a feasible solution in the midst of a live attack. And there are already indications that ransomware groups could be having less success monetising attacks.

The recent LockBit vs Royal Mail saga saw leak deadlines pushed back and ransom negotiations, which lasted almost two months, ultimately leading to non-payment (similarly to BlackCat’s recent failed efforts). Unsuccessful high-profile extortion efforts are terrible PR for ransomware and when you’re in the extortion business, maintaining a formidable public presence is vital.

With that in mind, reaffirming the depths that ransomware groups are willing to go via the cutthroat personal defamation of senior stakeholders may not only be a persuasive negotiation tactic but a necessary long-term strategy in terms of public perception.

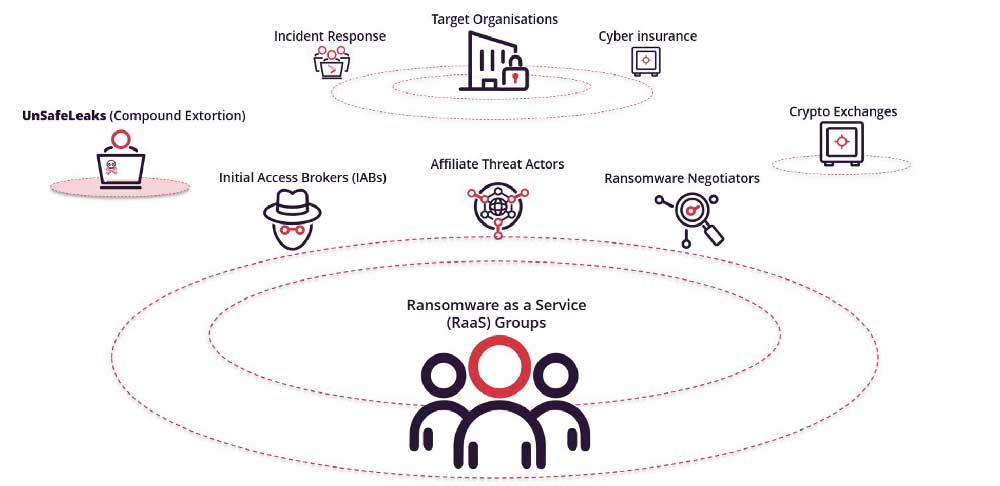

A simplified model of the current landscape from the perspective of a ransomware as a service (RaaS) group, such as BlackCat or REvil. On one hand, the emergence of compound extortion (i.e UnSafeLeaks) could be a welcome addition to RaaS groups and their affiliates. On the other, it could devalue ransom payments in the long run.

Furthermore, insurers have tightened clauses to limit their exposure to cyber attacks making less funds available to victims. Attacker revenues have reportedly decreased for the first time (down 40% in 2022), and while fluctuating, the exponential growth of annual attack rates also appears to have lessened.

With ransomware threat actors accustomed to estimated profits of ~$663 million on average over the past three years, breaking the typical rules of engagement by re-extorting victims and getting increasingly personal may be a logical strategy for RaaS groups experiencing their first downturn in revenue.

If the ransomware economy is shrinking as reported, threat actors’ strategies may well shift from formerly ambitious attempts to build a sustainable extortion model to a more direct ‘smash and grab’ approach that utilises the existing data of old attacks, especially if threat actors perceive that business is drying up.

What this means for targeted organisations

As a senior stakeholder, CISO, or CEO evaluating the implications of personalised compound extortion attacks, the idea of having not only your business threatened but your reputation tarnished or personal data exposed may be a daunting prospect. The current ransomware landscape is evolving, but there are steps that individuals and organisations can take to mitigate the risk of exposure.

First and foremost, JUMPSEC advise that whenever possible organisations should avoid paying a ransom, as initial payment is tacit indication that the target is primed for further compromise. If the reported struggles of ransomware groups are to be believed (i.e, diminished growth of attack rates, lower profits, and less margin to leverage insurance) perhaps this realisation is finally gaining traction within the industry.

UnSafeLeaks is also a practical reminder to senior leadership to be equally if not more vigilant when it comes to their personal security along with the overall security of their organisation.

Whilst increasing organisational resilience through advanced Incident Response programs, at-risk individuals need to take greater personal accountability and implement proactive security measures. For example:

- Ensure the separation of data to the appropriate personal or company devices i.e personal devices should not be used for company data and vice versa.

- Spread awareness to other at-risk individuals. Open lines of communication not only to senior leadership but all employees, and encourage them to report incidents without the fear of retribution, expanding the collective understanding of ransomware scenarios to encompass cyber bullying.

- Mitigate personal attacks on employees through the more familiar lens of insider threat risk mitigation (a well-established area with broadly overlapping protocols).

- Seek third-party security technical support to combat live incidents and ensure attackers are no longer present in the network, adhering to guidance from NCSC and legal counsel where necessary.

It is important to stress that UnSafeLeaks is not necessarily the next phase of ransomware. It may simply be an off shoot or a deviation away from typical ‘established’ RaaS groups’ activity observed thus far. However, JUMPSEC are not alone in documenting a recent trend towards increasingly personal attacks (for example recent reports on UNC3661 (Lapsus), UNC3944, and UNC3944).

It is therefore important to be aware that compound extortion can occur after an initial ransomware attack even if a ransom is paid, and to acknowledge the current trend towards highly personalised attacks on individual employees as a strategy which threat actors may continue to utilise.

Sean Moran

Enablement Manager

Sean is a researcher and writer with a specific interest in geopolitics and its impact on the cyber security industry.

John Fitzpatrick

Chief Technical Officer

As one of the UK’s foremost cyber security professionals, John's in-depth TI knowledge and experience enables industry-leading research and innovation.